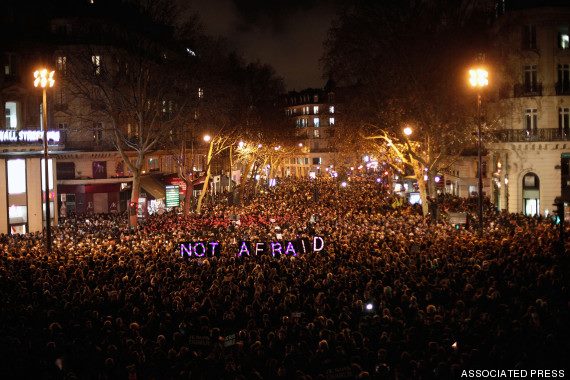

Not Afraid

On this day in 2015, terrorists murdered twelve journalists at a Paris-based satirical newspaper. That night, tens of thousands of Parisians rallied in a powerful demonstration of defiance and strength. In the following days and weeks—even as terrorist attacks continued (reaching a bloody crescendo that November, when 130 people were killed in coordinated attacks across the city and its suburbs)—the rallies grew progressively larger, eventually attracting millions. The slogan “Not Afraid” became a rallying cry.

In a self-contradicting and point-missing column published a day later, a Guardian writer argued that that “Not Afraid” slogans were ultimately a hypocritical pretense, intimating that the 2015 attacks would inevitably generate an “overreaction” while also arguing that, despite the terrorists’ own statements about acting on behalf of a hoped-for Caliphate, they could be seen as decades-delayed retaliation for National Police officers’ killings of Algerians in 1961. With a perverse or perhaps merely dialectical fatalism he concluded, “We are all prisoners of our history.”

Today’s pundits, in efforts to account for exploding ideological extremism in the West and the attendant (but which is the chicken and which is the egg?) surge of authoritarianism, wonder aloud whether the pandemic broke people’s brains (likely: it certainly damaged public trust, mainly in concert with the following phenomena), or whether social media is to blame (yes they are: more on that anon), or whether hostile foreign states have succeeding in their long (and long-avowed) game of undermining liberal democracies (absolutely, although not without enthusiastic support from inside, especially recently, on both ends of the political spectrum).

Still: I think the hapless Guardian columnist inadvertently put his finger on the pulse of the problem.

Liberal democracies—far and away the most innovative, productive, equal and inclusive polities—stand out because they enable us to not be “prisoners of our own history.” This is, of course, what dictators hate most about democracy, and why their regimes so reliably attack democracies. How can authority possibly be absolute; how can entire peoples be subjugated to the will of the leader; how can history itself be made into a monument to his power if people are free to make and remake their own futures?

Democracy’s unique strengths and the unique freedoms it enables do not mean democracies aren’t vulnerable. Too often we have squandered the dividends of democracy, treating it as an inexhaustible resource rather than a living entity that needs nurturing if is it to continue to offer sustenance. That this is a problem of the left as well as the right cannot be overstated.

We should have remained more vigilant. Now the hour grows late, and there is a rising torrent of attacks against democracy—from without and within—that calls on our courage to stand up and be Not Afraid to defend it.

Because if we are afraid to defend democracy now, we will find ourselves vastly more afraid without it.