During the lull between the years, when the nights were at their longest, I took stock of things and decided that, this year, I will focus on what may be mended.

In the world at large there is a storm: it is now all around us. The famous lines from Yeats have ever more relevance, only, this, time, it is impossible to say whether it is the best or worst who lack all conviction, are filled with passionate intensity, or are both at once. These are now the most visible symptoms of a great social ill threatening—determined, it seems increasingly clear—to destroy everything in its wake.

Margaret Atwood, whose essays appearing at In the Writing Burrow are among the most informed and cogent cultural analysis I have read in years, has issued a timely warning of what await us, unless we “call the bluff” that our societies are broken and can only be fixed by revolutions, terrorism, invasions or dictators. Atwood’s most immediate focus is on the upcoming US election, but her analysis applies anywhere democracy, due process and the peaceful transition of power are under threat.

In her commentary, Atwood points out that it is the aim of extremists on both the ultra-left and radical right to sow division, sabotage social accords, spread misinformation, undermine public institutions and elections and create chaos in what she calls “the temperate zone”—in political language this is often referred to as the centre or middle, but includes centre-left social democrats as well as small-c conservatives—in order to create opportunities to seize power.

In pursuit of these aims, extremists harness the dissatisfaction of ideological fellow-travelers, the genuinely aggrieved, and those who cynically anticipate, following the hoped-for revolution, uprising or seizure of power, to be appointed to positions of authority themselves. Their rhetoric becomes increasingly radical and ever more authoritarian. Anyone who questions the ideological imperative is an enemy. The divisions deepen. Rakoth Maugrim—the Unraveler, the Destroyer, the self-appointed bearer of Vengeance—steps in and seizes the world in his teeth.

Unless ordinary citizens refuse it.

I refuse it. And so can you.

It is not even all that difficult to do. One good way to begin is by muting the ideologues who—most often via social media but also, increasingly, in progressive as well as conservative faith communities, political organizations and, depressingly, educational environments—spread the poison of the movements they have attached themselves to. Watch for their absolutism, and for their calls for obedience to cult-like kinds of fundamentalism. And mute them; banish their invented or exaggerated claims, their one-sided narratives, the propaganda they reshare, their exhortations to burn everything down. Halt their takeovers of your communities, and their silencing of anything that sounds even remotely like dissent. Do this even to the ideologues on your own ‘side.’ Do it even to yourself, because chances are good you too have contributed to the ideological dumbing down of our society.

When you do this it’s actually amazing how quickly the airwaves quiet. All at once there is room to breathe, time for perspective, an opportunity to weigh your own thoughts alongside the experiences and perspectives of others, and a chance to notice all the other people who, likely a lot like you, both build and benefit from the social institutions extremists want to use you to destroy.

It’s okay to be critical. Our society is imperfect. There is much that may be improved. But anyone who says it must all be burned down and remade in their name or in the name of their ideology is not interested in improvement.

During the lull between the years, sickened by the news and nauseated at the rhetorical spewage on social media and in one of the communities I belong to, I set aside my laptop. Instead I brought down my sewing box, set it up beside the old wooden table in our kitchen, and, in peaceful silence on a dark winter night, the kitchen warm, the dinner dishes washed and drying behind me, set to work mending what could be mended.

Mending is about much more than sewing up seams, and it would be foolish to pretend that mending a beloved winter coat I’ve had for 25 years has much to do with repairing the world.

But I am a person who believes that the things we do as individuals have resonance far beyond ourselves, and that it is not only big acts but small ones that make the world. Small acts are actually practice for larger ones, in the sense that the way we do small things usually parallels the way we do larger things.

Not all things may be mended. Some things are too broken to fix. But a great deal may be repaired, and much that may be mended exists in the spaces between us—in our personal relationships, in the civility we owe to our communities, and in our duty of care to the natural environment. And if we are able to be mindful of these nearby things, we might also appreciate the virtues of stable democracies and their social contracts, and the separation of church and state, and the close connections between innovation and prosperity, and the benefits of charity, and civil liberties, and so on.

Yes but!, I can sense you saying. Yes but!—late capitalism is evil, communists are everywhere, carbon taxes are destroying the economy, the planet is burning, a drag queen is reading stories at the library, a stranger misgendered me, the deep state is watching us, big pharma vaccinated my dog, pop singer psy-ops, settler colonialism, the lamestream media, chatbots, 15-minute cities, megachurches, stolen elections, Superbowl shootings, the unborn, the undead.

Hush.

In an excellent recent essay on the excess of noise—literal and figurative—in contemporary culture, and on the urgent need for quiet, cultural commentator Michael Harris observed that

[S]ilence leaves room for the development of a rich interior life, for daydreaming and the formation of an identity independent of the hive mind. Our personalities mature in the empty spaces that allow them to self-reflect; we discover what we really think or really feel when inputs hush and we can sit a while with what we’ve already received. In this way, amid doses of quiet and stillness, the self coheres.

If the loudest mantra of the moment is “burn it all down,” then the mantra of those of us interested in mending should be “turn it all down,” and “tone it all down.”

Turn down the ideologues, especially on the social media platforms whose algorithms promote extremism via ‘engagement’ and ‘reach.’ Tone down your own propensity to be persuaded by one-sided rhetoric and oversimplified narratives. Stop making everything about politics (and maybe consider: When did choosing what to read, watch, attend and value become principally a performative expression of political identity? And what has doing so cost us in terms of perspective?).

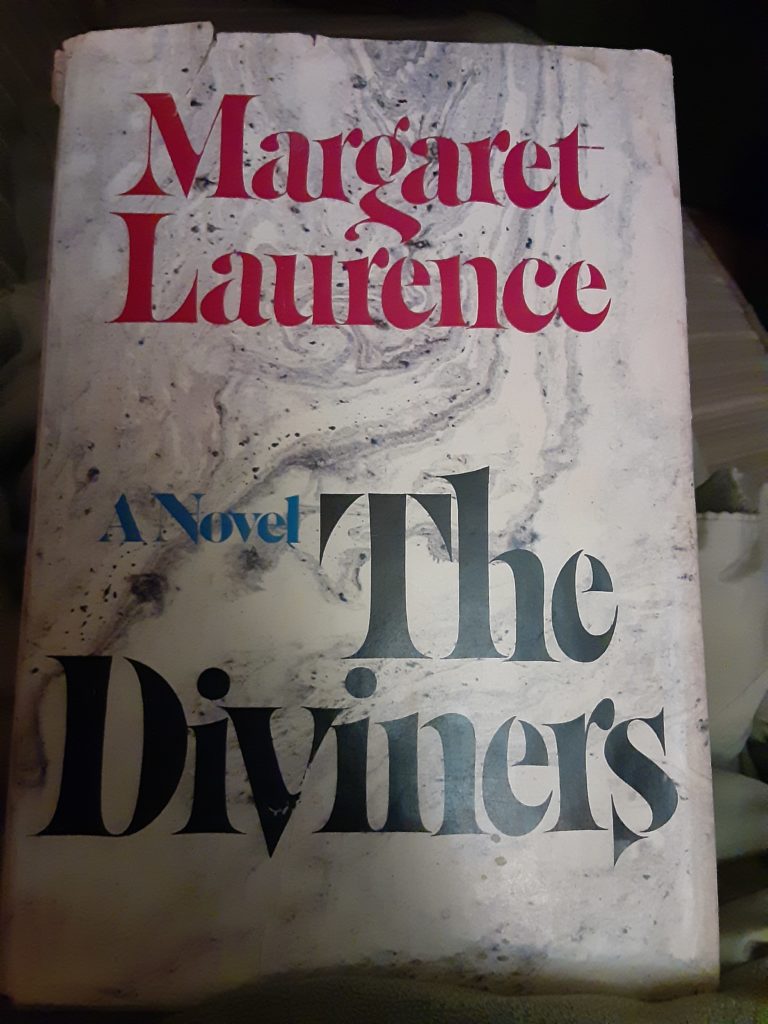

Put down your phone. Go for a walk. Pet a cat. Talk to a dog. Smile at a baby. Pick up some litter. Say hello to a stranger on the street. Get up early. Look at the sunrise (no: really look at it). Stay up late, and listen (even for just a few moments) to the wind roaring in the trees, or to the silence, or to cars on the highway, or to those tiny rustles in the grass. Grow something (in a pot, on your balcony, in your yard, or in a nearby park). Pick a dandelion. Thank a bee. Go to a bookstore or a library. Read a poem. Remember, even if only for a few moments, how fortunate you are—how fortunate we all are—to have been born in this corner of the expanding universe.

Mend something.