Vintage Finds | Flower Power Bathtub Decals

Whatever happened to bathtub decals? You know, those Mod peel-and-stick shapes that were a feature of many North American bathrooms in the 1970s, as ubiquitous as decorator toilet paper and avocado-coloured fixtures? Where did they go? When did they fall out of fashion? And why, nearly 50 years later, do they still sometimes show up at thrift stores?

When I was a kid, almost everyone’s house, even ours, had peel-and-stick decals in the bathtub. Marketed as a safety device meant to reduce the risk of slips and falls, the decals had the added benefit of upping the decor quotient in an otherwise prosaic room. After the Second World War, woolen mills marketed matching towel sets (under brand names like Fieldcrest and Royal Cannon) to newlyweds setting up households in smart suburban ranch houses, and by the 1960s every department store carried entire lines of bathroom accessories — towels, washcloths, bathmats, even toothbrush holders in coordinating colours. By the later 1960s and especially in the decadent seventies, bathrooms received what in retrospect was completely over-the-top decorating attention, complete with wall-to-wall carpet and heavy drapes. Bathtub decals offered a way for budget-conscious householders to participate in these maximalist decorating trends.

[P.S. In 1981 my parents bought an otherwise modest bungalow in a Toronto-area suburb that had received the full 1970s treatment in the same way a junker car might have a thousand dollar stereo, complete with stuccoed walls (painful!), garish purple wallpaper in loud Mod designs, and wall-to-wall carpet in the everything-Harvest-Gold main floor bathroom. My mother’s solution to the sanitary challenge of shag carpet around the toilet was to cut it into sections that could fit into the washing machine for semi-regular cleaning. The bungalow and its hideous wallpaper are long gone, and it’s a real pity there’s no photographic evidence of its colourful if rather chaotic heyday.]

Bathtub decals continued to be marketed into the 1980s, albeit in relatively subdued colours and patterns, and seem never quite to have disappeared, but never since have they regained their primacy as a standard decor element in North American bathrooms. I am guessing an eighties-era rejection of everything the seventies represented was part of this, followed by shifts in bathroom design in which stand-alone showers and clean lines have dominated ever since. There is also the challenge of keeping the decals from accumulating disgusting bathtub crud, which may be why there are more online instructions for removing old bathtub decals than for choosing them.

With renewed interest in the more kitschy elements of late midcentury design, it seems that bathtub decals deserve a revival. Maybe not on the bottom of the tub, although they might be cute on the outside of a glass shower door or on a tiled wall. They could even be great mounted on a kitchen backsplash, or on a laptop computer. It’s not out of the question that a few colourful decals could have softened the public response to this recent bathroom-related controversy.

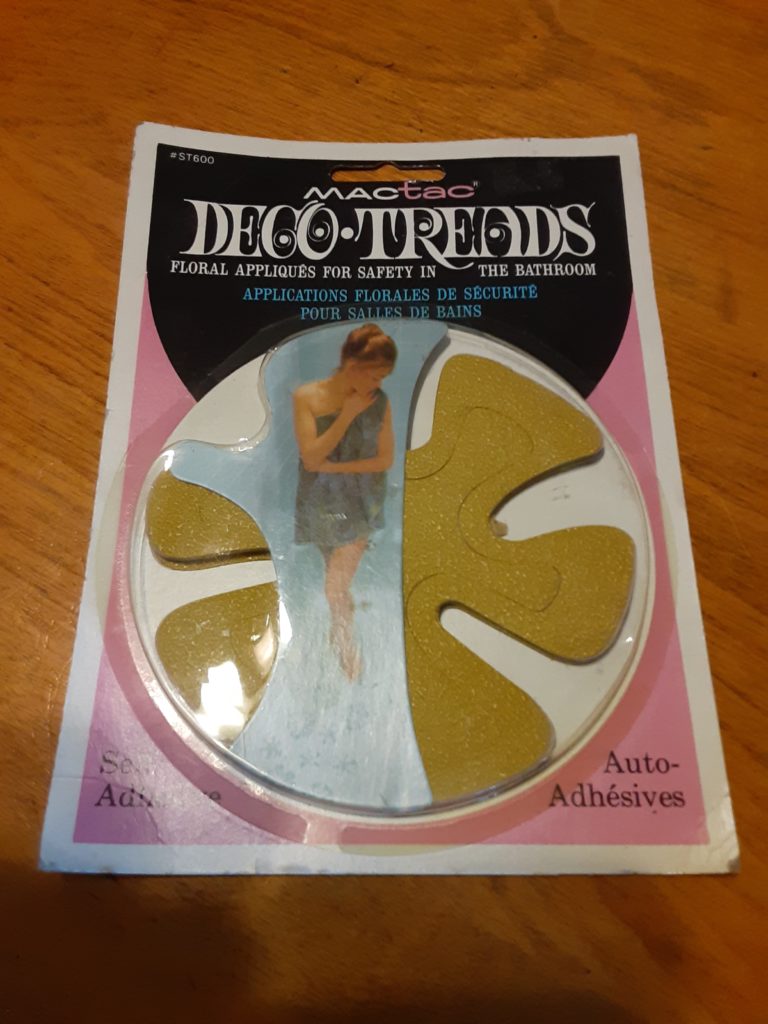

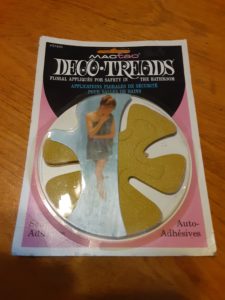

I have two new-in-package sets of vintage bathtub decals, both of 1970s vintage. The green hued (one might say … avocado) ones were made by Rubbermaid (manufactured at Rubbermaid Canada’s Mississauga plant) and appear to date to 1975. I picked these up at Value Village the other day. The harvest gold ones (thrifted a few years ago) are also daisy-patterned and were part of the Mactac line of products made by Morgan Adhesives of Canada Limited in Brampton, Ontario. Both sets of decals were manufactured here in Canada, at plants whose parent companies, unusually, appear to continue operating manufacturing operations in this country. Increasingly long gone, however, are the days when a high school education could still get you a decently paid factory job with benefits — possibly including an employee discount on decorator bathtub decals.

Vintage Finds | Flower Power Bathtub Decals Read More »