Treasures from the Victoria College Book Sale, 2023 Edition

Every September my pulse quickens as book sale season rolls around. Book sale season is, of course, the time of year when the University of Toronto’s colleges hold fundraising sales—collectively known as Bibliomania—to support their libraries and other college projects. The books are donated, and include castoffs and sometimes entire collections from Toronto’s bookish set—university faculty, readers, writers: anyone who loves the printed word but finds a need to cull a few shelves. The sales are massive and attract huge crowds, particularly on opening day when the lineups even before opening can be hundreds of people long.

I started attending the UofT book sales as a grad student, and became a regular while working on a Toronto-focused research project. When my daughter was a newborn 15 years ago, I brought her into the Victoria College book sale in a chest carrier, and jostled with her down the aisles while wondering how many books I could stuff into the stroller I’d checked outside. Quite a few, it turns out, although I remember it listing a little on the subway.

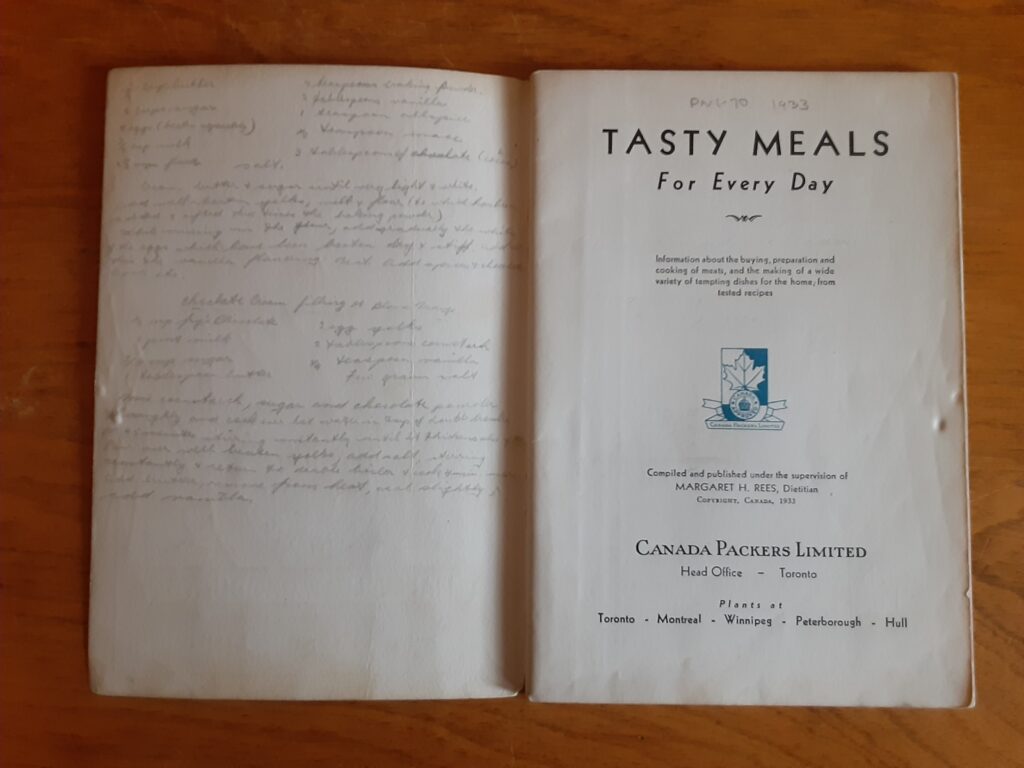

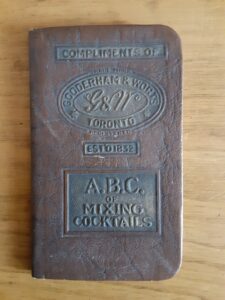

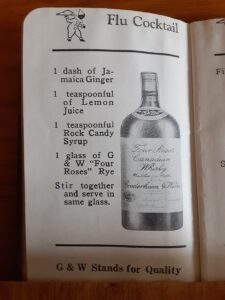

These days I look for two kinds of books: domestic manuals, decor guides, and old cookbooks dating up to the mid-1950s, for another research project; and just generally quirky books that suit some of my more ridiculous sensibilities. I love that weird old books are still out there for the finding.

The Victoria College Book Sale was a couple of weeks ago. I always try to go as early as possible to get a decent place in line, but this year I was only able to get to Vic about an hour before the sale started, and as a result was quite far back in line. Still, I managed to get into the ‘specials’ room (rare, antique, quirky) immediately upon opening, and after that was able to navigate the crowds through the large halls where most of the sale is held fairly easily, digging through the well-sorted boxes with tremendous joy.

Some of this year’s special finds:

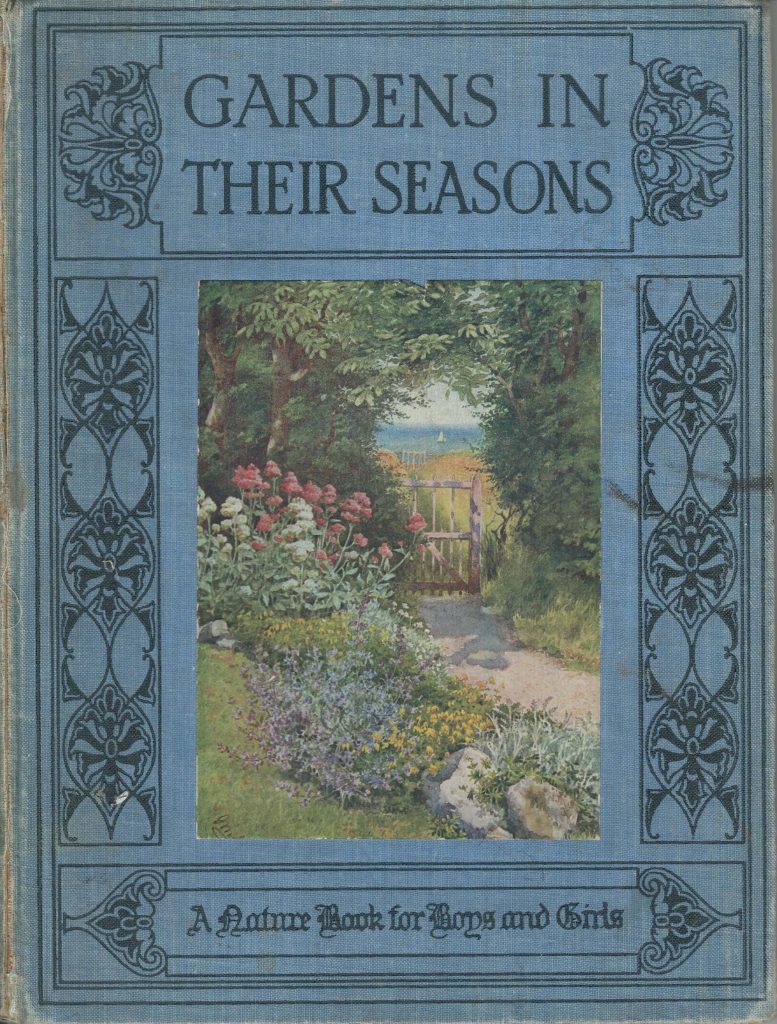

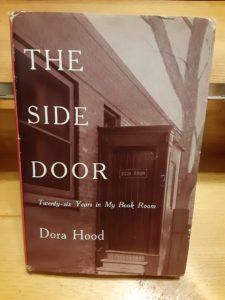

I don’t think I had never heard of Dora Hood or her ‘Book Room,’ which Hood operated on Spadina Avenue near Bloor from 1928 to 1954 before retiring and selling the business to successors (who, variously, ran the business until it closed in 1981). The Side Door: Twenty-Six Years in My Book Room (Ryerson Press, 1958) is an unassuming-looking book with a rather uninteresting title—but is actually a fascinating read. I bought The Side Door mainly because I didn’t have it already, and because I was mildly interested in what the author might have to say about bookselling in Toronto during her era.

I don’t think I had never heard of Dora Hood or her ‘Book Room,’ which Hood operated on Spadina Avenue near Bloor from 1928 to 1954 before retiring and selling the business to successors (who, variously, ran the business until it closed in 1981). The Side Door: Twenty-Six Years in My Book Room (Ryerson Press, 1958) is an unassuming-looking book with a rather uninteresting title—but is actually a fascinating read. I bought The Side Door mainly because I didn’t have it already, and because I was mildly interested in what the author might have to say about bookselling in Toronto during her era.

Hood was a purveyor of rare and antiquarian books, and a renowned dealer in Canadiana. Her memoir details a selection of these books with relish, making it a kind of catalogue in itself. Hood’s stories about how she acquired books, and from whom, and to whom she sold them, are amazing and envy-inducing. Hood lived a remarkable life, and her contributions to the book trade, to the preservation of old books, and to Canadian history scholarship more generally, were immense.

While researching Hood and her Book Room, I was unsurprised to see that Toronto historian Jamie Bradburn (a fellow book hound whom I run into at nearly every book sale) has previously written about her life and times: please visit Jamie’s blog to learn more about Hood, her shop, and her era.

[P.S. Looking at the font on Dora Hood’s advertising makes me think I have seen it somewhere … possibly on a bookmark found, perhaps appropriately, in an old book.]

*

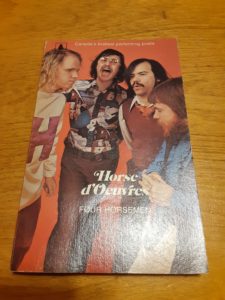

A completely unexpected find this year was Horse d’Oeuvres (PaperJacks / General Publishing, 1975)—a collection of works by avant-garde Canadian sound poets The Four Horsemen … published in a mainstream pulp paperback of the sort one could have bought at any Coles Bookshop or even the local drugstore. And not that kind of drugstore, either. It blows my kind that there was ever a time, in Canada or anywhere, really, when weird poetry could produce mainstream publishing success.

A completely unexpected find this year was Horse d’Oeuvres (PaperJacks / General Publishing, 1975)—a collection of works by avant-garde Canadian sound poets The Four Horsemen … published in a mainstream pulp paperback of the sort one could have bought at any Coles Bookshop or even the local drugstore. And not that kind of drugstore, either. It blows my kind that there was ever a time, in Canada or anywhere, really, when weird poetry could produce mainstream publishing success.

The Four Horsemen were Rafael Barreto-Rivera, Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery, and bp Nichol. Nichol is perhaps the best known of the Horsemen outside poetry circles, having published prolifically across genres and having contributed extensively to children’s television programming, but all four were gifted, multidimensional poets and performers. The works in Horse d’Oeuvre are strong and varied, and wow: I’d have loved to be a 14 year-old coming across a book like this while spinning a paperback rack at the local pharmacy, because this was about the age I started producing, on the heavy old manual typewriter in my bedroom, things (‘compositions’ would be too strong a term) I called ‘pomes,’ which played with words, syllables, and the space on the page. I had no idea these textual / spatial experiments even counted as creative work, however, and soon gave them up, not knowing I was making crude attempts at concrete / visual poetry.

Of all the pieces in Horse d’Oeuvre, I think my favourite is Paul Dutton’s ‘this is a poem:’

this is a poem for my father’s gravestone

a grave poem for my father’s stone

a father for my poem’s gravestone

a groan for my father’s grave

[….]

Dutton’s poem is deeply (pre-post) modern, but also reminiscent of eighteenth century poets in its cadences and tone (an elegy of sorts, it of course reminds one of Thomas Gray).

Bonus: my copy is signed by two of the Horsemen (by Dutton; and by McCaffery, who inscribes his section, via a simple code, to Mary) although not, sadly, by bpNichol. [Although to be frank, bpNichol’s poems in this collection are among his more self-indulgent, and lack some of the vital fervor of his subsequent work.]

*

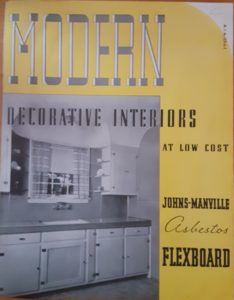

I have an enduring love for twentieth century design of the pre- and immediately post-war period. There is something about the clean lines and pale, earthy tones that seems fresh and genuinely modern. This promotional guidebook is from 1938, and features Asbestos (!) Flexboard suitable for use in commercial as well as residential settings. The brochure references the 1934 National Housing Act (US), which was New Deal era legislation intended to reduce foreclosures, and which also provided and insured loans for home repairs.

I have an enduring love for twentieth century design of the pre- and immediately post-war period. There is something about the clean lines and pale, earthy tones that seems fresh and genuinely modern. This promotional guidebook is from 1938, and features Asbestos (!) Flexboard suitable for use in commercial as well as residential settings. The brochure references the 1934 National Housing Act (US), which was New Deal era legislation intended to reduce foreclosures, and which also provided and insured loans for home repairs.

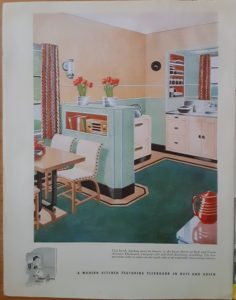

Behold the colour tints available: “rich and distinctive” Rose, Green, Light Gray (a “shade of unusual adaptability”), “admirable” Buff, and Slate. I also love the concept kitchen (in Green and Buff) with its streamlined appliances, colour-coordinated canisters and nook for radio and cookbooks.

Behold the colour tints available: “rich and distinctive” Rose, Green, Light Gray (a “shade of unusual adaptability”), “admirable” Buff, and Slate. I also love the concept kitchen (in Green and Buff) with its streamlined appliances, colour-coordinated canisters and nook for radio and cookbooks.

Did any real people have this sort of decor in their actual kitchens in the late 1930s? While I’ve seen concept kitchens of this sort in quite a few magazine spreads of this era, I don’t think I’ve ever seen an archival photo of a real, lived-in kitchen like this. I wonder if the tail end of the Depression, followed so quickly by the war with its attendant restrictions on non-essential manufacturing, meant these concept kitchens were destined to remain dreams. There are hints of these stylings in 1950s diner-era kitchens, but after the war modernism turned in different directions—to international influences, or to kitsch. The cool, clean stylings of the 1930s seem to have vanished.

*

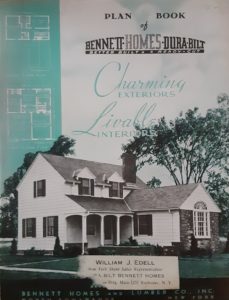

Another, related, find was this Plan Book of Charming Exteriors and Livable Interiors, produced in 1938 by Bennett Homes and Lumber Co. of upstate New York. Books of home plans were common until the early 1960s (Sears Roebuck being the best known); from these books, property owners could order entire house-building kits, including architectural plans and all lumber pre-cut to size. This book includes 50 home plans, most of modest size, with two or three bedrooms.

and Livable Interiors, produced in 1938 by Bennett Homes and Lumber Co. of upstate New York. Books of home plans were common until the early 1960s (Sears Roebuck being the best known); from these books, property owners could order entire house-building kits, including architectural plans and all lumber pre-cut to size. This book includes 50 home plans, most of modest size, with two or three bedrooms.

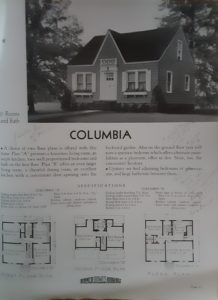

The original owner of my brochure marked house designs of special interest to her, and appears to have settled on the Columbia, a fairly simple 1 1/2 story home with a gable over the front door. From her notes it appears that a complete kit for the Columbia (plans, lumber, and kitchen cabinets) could be bought for $3,769, and financed at 3 1/2 percent. Her annotations include notes about additional costs, estimated as follows: “Mason Work 750.00, Plumbing 450.00, Wiring 125.00, Heating 250.00, Painting 225.00, Carp(entry) labor 600.”

I f the costs for this home seem low—in 2023 dollars, $3,769 works out to a little over $81,000—it is worth noting that this amount covers only the architectural drawings and lumber. It would not include HVAC, plumbing, wiring or foundation work–all costs that would now be many magnitudes greater than the estimate indicated by the prospective homeowner. Nor would it include the cost of the land. The 1938 design, however quaint, would also not conform to contemporary building codes in terms of structure or insulation.

f the costs for this home seem low—in 2023 dollars, $3,769 works out to a little over $81,000—it is worth noting that this amount covers only the architectural drawings and lumber. It would not include HVAC, plumbing, wiring or foundation work–all costs that would now be many magnitudes greater than the estimate indicated by the prospective homeowner. Nor would it include the cost of the land. The 1938 design, however quaint, would also not conform to contemporary building codes in terms of structure or insulation.

Still, the Columbia, like the other house plans in this brochure, is lovely and deeply evocative of its era. Unsurprisingly, it turns out that there is a fair amount of historical interest in Bennett house plans–here’s an interesting account, complete with images, of the Dresden, another of the Bennett kit houses, and here’s some more commentary on Bennett’s 1920s offerings. And click here for home plans from a variety of manufacturers.

*

To my small library of practical guides of yesteryear I add Handy Farm Devices and How to Make Them (1909; 1928). It is a dear little book with a lovely, arts-and-crafts-inspired cover and interesting illustrations accompanying instructions for (among many other devices) devising sawhorses, sowing machines, fruit picking devices, adjustable clotheslines, and smokehouses. I’ve added it to my bookshelf, alongside Boot Making and Mending (1898; 1912) and Practical Buttermaking (1924), because after the zombie apocalypse these skills, alongside blacksmithing, dowsing and witch hunting, will probably come back into vogue.

1928). It is a dear little book with a lovely, arts-and-crafts-inspired cover and interesting illustrations accompanying instructions for (among many other devices) devising sawhorses, sowing machines, fruit picking devices, adjustable clotheslines, and smokehouses. I’ve added it to my bookshelf, alongside Boot Making and Mending (1898; 1912) and Practical Buttermaking (1924), because after the zombie apocalypse these skills, alongside blacksmithing, dowsing and witch hunting, will probably come back into vogue.

*

The Hawks and Owls of Ontario (revised edition; 1947) was one of my favourite finds at the Victoria College Book Sale. It is a charmingly illustrated guide published by the Royal Ontario Museum of Zoology during that long and sadly long gone era in which governments and cultural institutions made efforts to share accessible information about Ontario’s flora, fauna, fossils and geology as an important part of public education. My copy is signed by its author, Lester Lynn Snyder, a noted ornithologist, “curator of birds” at the ROM, and co-founder of the Toronto Field Naturalists.

The Hawks and Owls of Ontario (revised edition; 1947) was one of my favourite finds at the Victoria College Book Sale. It is a charmingly illustrated guide published by the Royal Ontario Museum of Zoology during that long and sadly long gone era in which governments and cultural institutions made efforts to share accessible information about Ontario’s flora, fauna, fossils and geology as an important part of public education. My copy is signed by its author, Lester Lynn Snyder, a noted ornithologist, “curator of birds” at the ROM, and co-founder of the Toronto Field Naturalists.

It’s very interesting to note that some of the birds of prey once reported uncommon and in decline in Southern Ontario, mainly due to deforestation (and, later, pesticides)—e.g. sharp-shinned, Cooper’s, and Red-tailed hawks, and peregrine falcons—are now seen regularly in this part of the province, having adapted to urban life and benefitted from cosmetic pesticide bans in cities. If only the many other animal species now in decline could enjoy such comebacks. I love the cute saw whet owl on the cover — a bird I’ve never seen in real life.

*

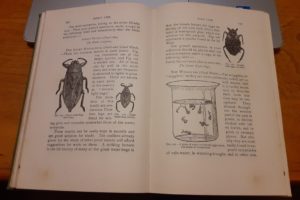

Insect Life: An Introduction to Nature Study (1919) was written principally for middle-grade school children interested in exploring outdoor life. The book, which is organized by locale (various chapters are titled ‘Pond Life,’ ‘Brook Life,’ ‘Orchard Life,’ ‘Forest Life,’ and ‘Roadside Life’), encourages students to venture out into natural environments to observe insects in their natural habitats, and sometimes to collect and mount them.

Insect Life: An Introduction to Nature Study (1919) was written principally for middle-grade school children interested in exploring outdoor life. The book, which is organized by locale (various chapters are titled ‘Pond Life,’ ‘Brook Life,’ ‘Orchard Life,’ ‘Forest Life,’ and ‘Roadside Life’), encourages students to venture out into natural environments to observe insects in their natural habitats, and sometimes to collect and mount them.

Books like this challenge the commonly held view that, until the rise of critical pedagogical theory in education, all learning had been rote learning, and consisted mainly of memorization and repetition. Much of it was, but in the natural sciences at least, Darwin’s investigations prompted several generations of educators and natural science writers to see nature as a classroom, and science as a subject best explored in the field.

It’s a pity this approach is no longer standard in elementary schools. Budget cuts, risk aversion and ideological intrusions from the left (e.g., the rise of critical animal studies) and right (especially among religious fundamentalists seeking to replace science with theology) have made educators reluctant to have students do more than look at YouTube videos and memorize taxonomy. It seems to me that kids would be far better equipped to handle the very severe environmental challenges of our era if they knew a little bit more about how ecosystems actually work from spending time out exploring them.

*

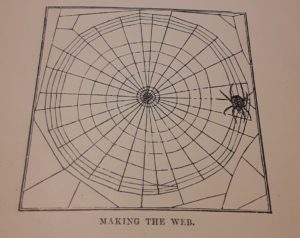

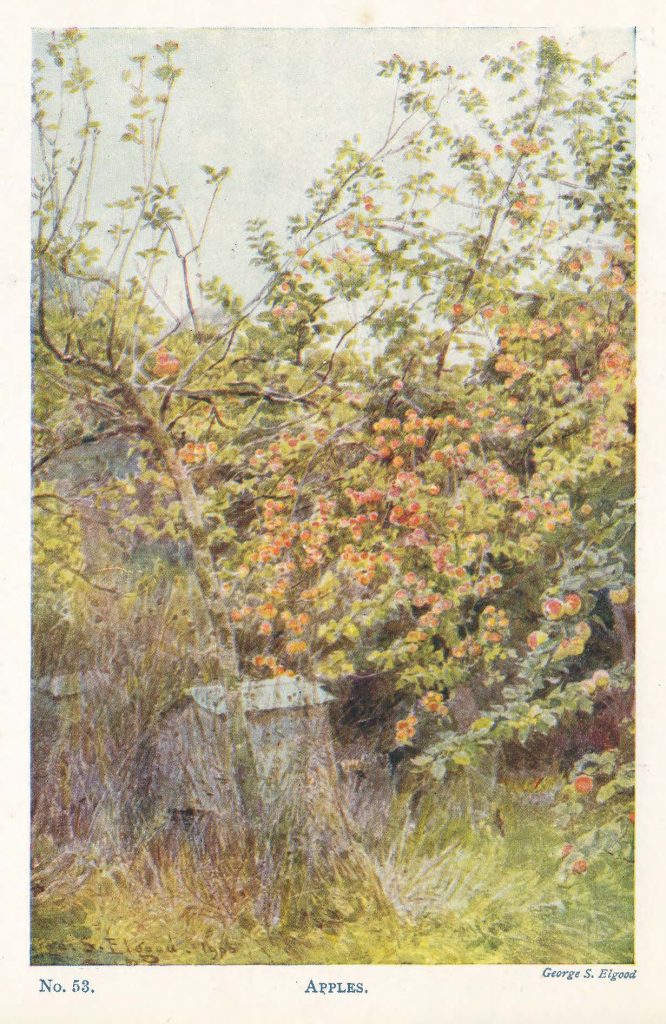

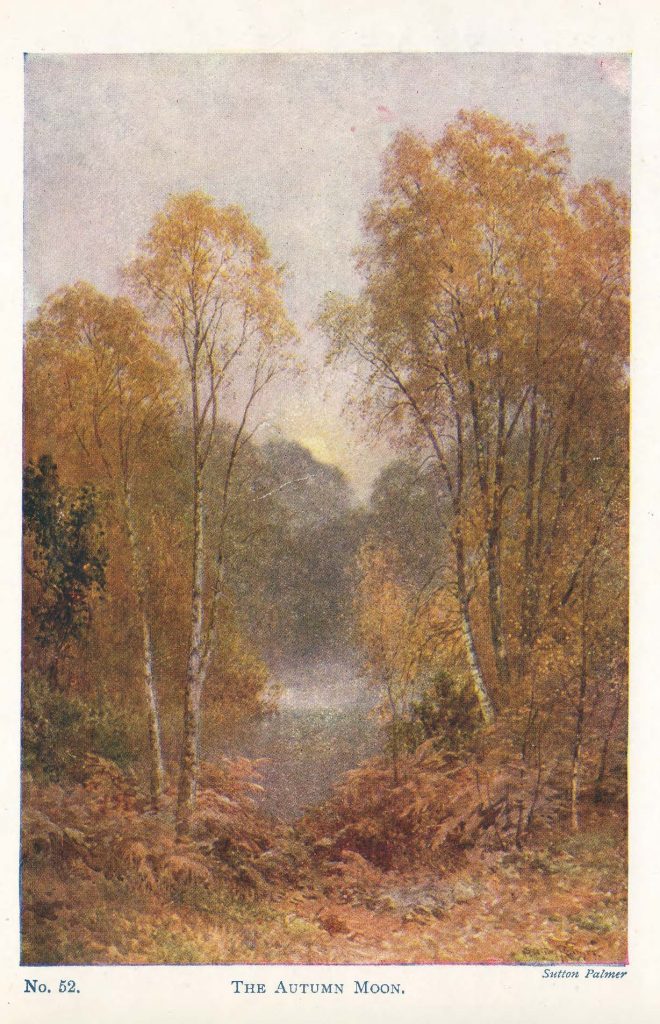

The Natural History of the Year (1896; 1901) is a delightful guide, written for young people, to nature throughout the seasons. It is charmingly illustrated and slightly florid in its language—but no less intelligent for it. The author cites the discoveries of numerous 18th and nineteenth century naturalists and recommends scientific works for further reading, even while quoting bits of doggerel and comparing winter to the story of Sleeping Beauty.

The Natural History of the Year (1896; 1901) is a delightful guide, written for young people, to nature throughout the seasons. It is charmingly illustrated and slightly florid in its language—but no less intelligent for it. The author cites the discoveries of numerous 18th and nineteenth century naturalists and recommends scientific works for further reading, even while quoting bits of doggerel and comparing winter to the story of Sleeping Beauty.

At the same time, the book is definitely influenced by late Victorian sensibilities, as this text on the withering of leaves in the fall suggests:

But there is something very beautiful in the manner of their dying. For before they fall they surrender all their worldly goods to the plant which bore them; all the useful material–sugar, green pigment, more complex substances, and living matter itself—retreats into winter quarters in stem or root.

*

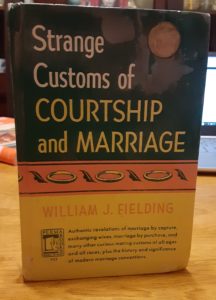

I will include one final treasure before this post gets any longer. It is Strange Customs of Courtship and Marriage (1942; 1949), written by William J. Fielding, apparently a noted American sexologist, albeit one who left school before finishing grade 8. But, presumably with an adolescent’s fascination for all things sexual, this autodidact seems to have spent his life researching and writing about sex—his side gig while also working as a secretary at Tiffany’s.

I will include one final treasure before this post gets any longer. It is Strange Customs of Courtship and Marriage (1942; 1949), written by William J. Fielding, apparently a noted American sexologist, albeit one who left school before finishing grade 8. But, presumably with an adolescent’s fascination for all things sexual, this autodidact seems to have spent his life researching and writing about sex—his side gig while also working as a secretary at Tiffany’s.

Strange Customs of Courtship and Marriage was originally published in 1942 and appears to have been reprinted repeatedly up until the mid 1960s. It is one of a number of rather surprisingly well-researched books about salacious or at least eyebrow-raising subjects published for general audiences in inexpensive pocket paperback editions, among them Daniel P. Mannix’s A History of Torture and Burgo Patridge’s A History of Orgies.

Treasures from the Victoria College Book Sale, 2023 Edition Read More »