I am very fond of old natural history books, particularly those published prior to about 1910. They are usually charmingly written, often perspicacious in their discussions of science, and almost always beautifully printed and illustrated.

I am very fond of old natural history books, particularly those published prior to about 1910. They are usually charmingly written, often perspicacious in their discussions of science, and almost always beautifully printed and illustrated.

Tenants of an Old Farm: Leaves from the Note-book of a Naturalist (which I bought for $20 at last year’s Trinity College Book Sale) is a splendid example of this type of book. Originally published in 1884 (my copy the Third Edition of 1886), it was written by Henry C. McCook (1837-1911), a noted American naturalist and (Presbyterian) clergyman. McCook was, among many other things, an expert on ants and spiders. He published eight books on insects and nearly a dozen on theology—a particularly interesting confluence in the wake of Charles Darwin’s work on natural selection.

And indeed, evolution—and Darwin himself—are referenced in Tenants of an Old Farm. In a chapter on burrowing insects, the narrator (McCook himself, the reader presumes) probes into a farm visitor’s views on evolution , hoping to spur an argument:

“Perhaps, I suggested, thinking to draw the Doctor’s theological fire, “The insect is a far-away ancestor of the vertebrate? At least, an evolutionist might have no difficulty in accounting for such resemblances by some application of this theory.”

The Doctor surprises the narrator by supporting the proposition:

The Doctor glanced slily at me, smiled, and answered: “Ah! you shall not disturb my equanimity so. Evolution is no theological bête noir to me. Not that I believe it all; on the contrary, I think it is yet an unproved hypothesis. But, considered as a method of creation simply, I am willing to leave it wholly in the hands of the naturalists and philosophers. Of course, that materialistic view of evolution, which dispenses with a Divine Creator as the First Cause of all things, has no place in my thought. That is not for a moment to be tolerated; but, as for the rest, why should Christian people disturb themselves? Science has not yet said her last word, by any means, and we can well afford to wait.”

In this way, McCook introduces and quells the theological argument against evolution while deftly modeling the method of science: weighing theories in light of the available evidence and remaining open to new explanations.

Later, in a chapter titled ‘The History of a Bumble-Bee,’ the narrator directly references “the late Mr. Darwin [and] his book on the “Origin of Species” in a discussion of co-evolved relationships among living things:

We may infer, he says, as highly probable, that were the entire genus of bumble-bees to become extinct or very rare in England, the heart’s-ease and red clover (which they fertilize by carrying pollen from flower to flower), would become very rare or wholly disappear.

Given that some religious leaders remained hostile to the emerging science, viewing it as a threat to Biblical teachings, McCook’s handling of the subject comes across as nuanced and refreshingly balanced. Would that such differences could be handled nearly as deftly in this ideological age!

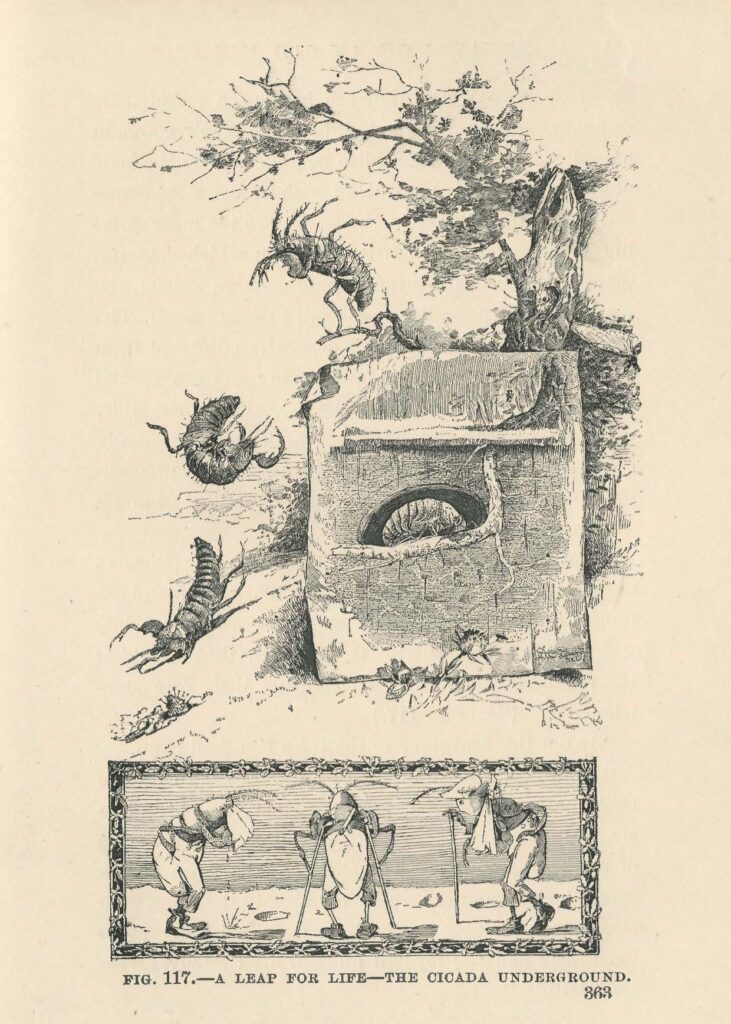

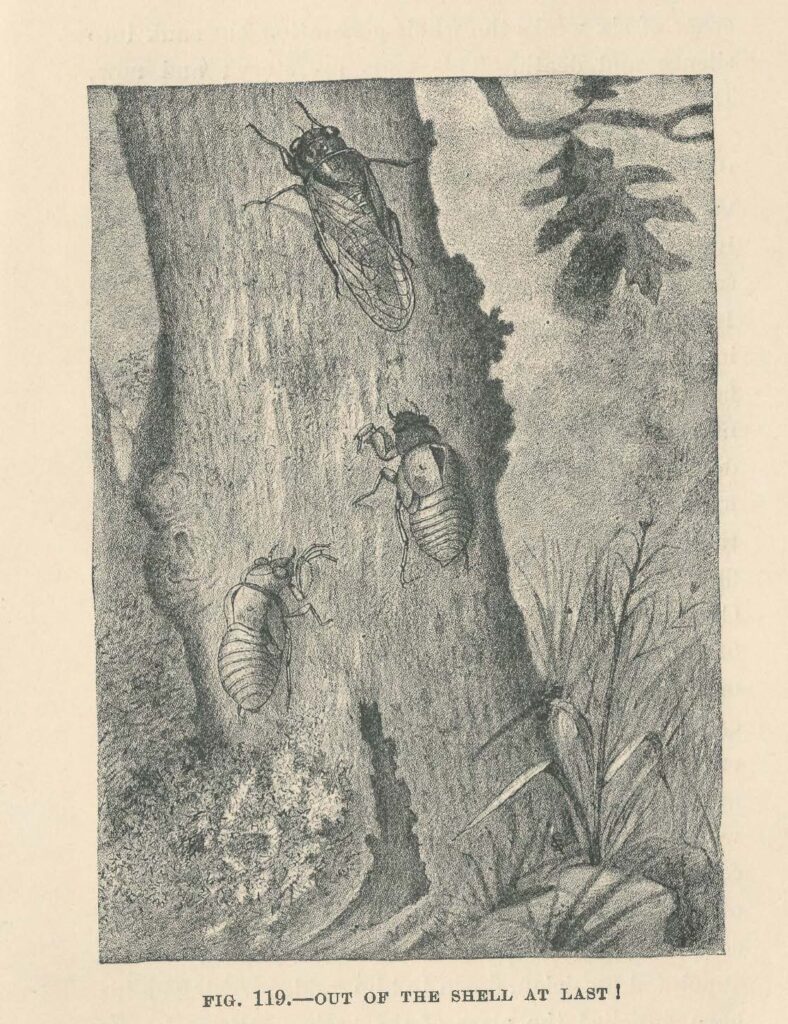

The book’s illustrations are detailed and often amusing. Look at these images showing the life-cycle of the cicada:

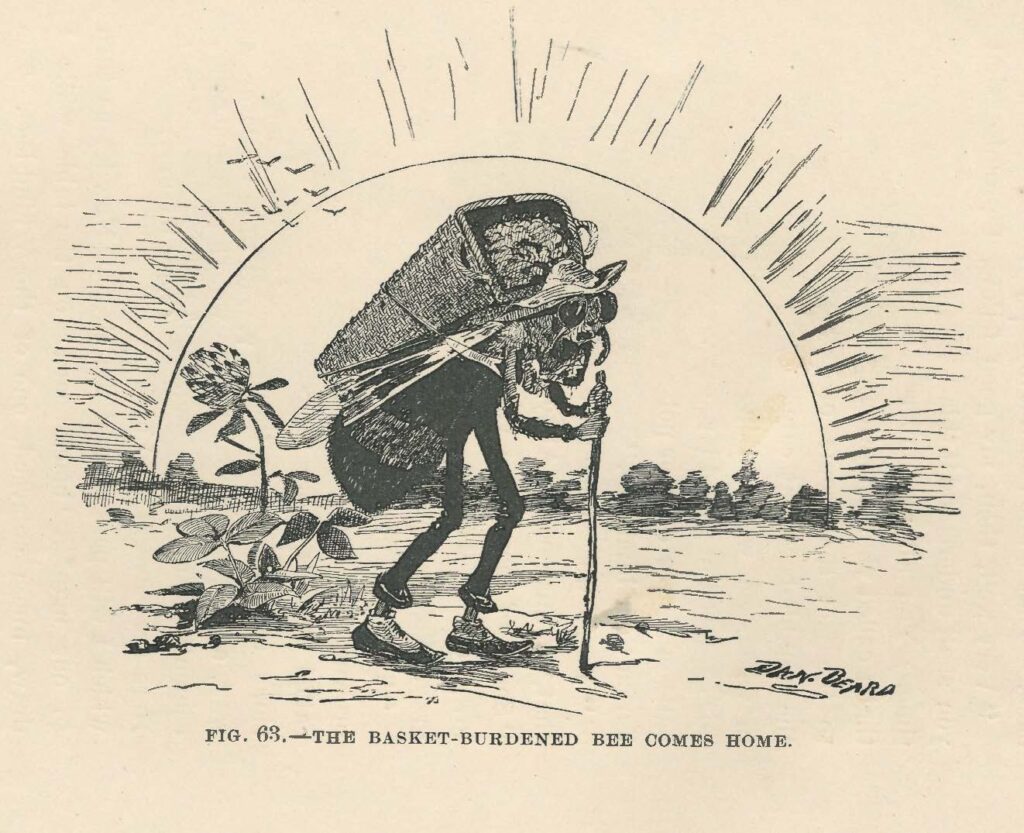

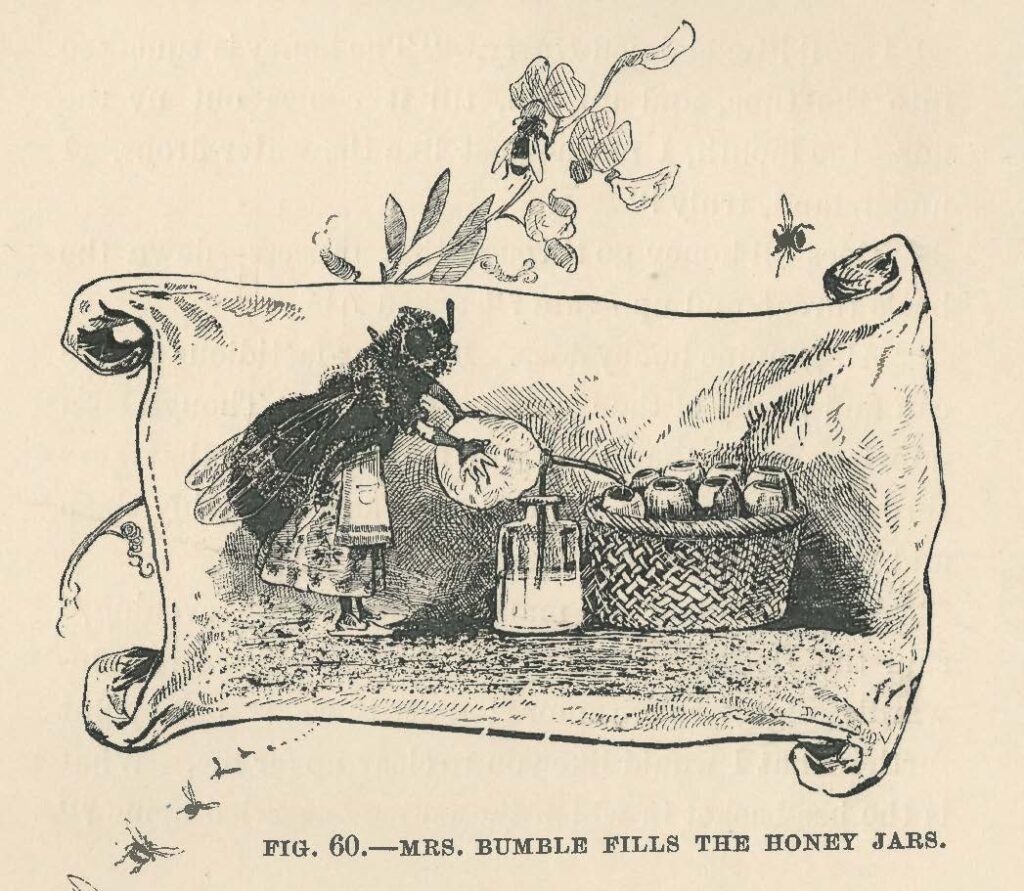

… and these highly anthropomorphic images of the hard-working bumblebee:

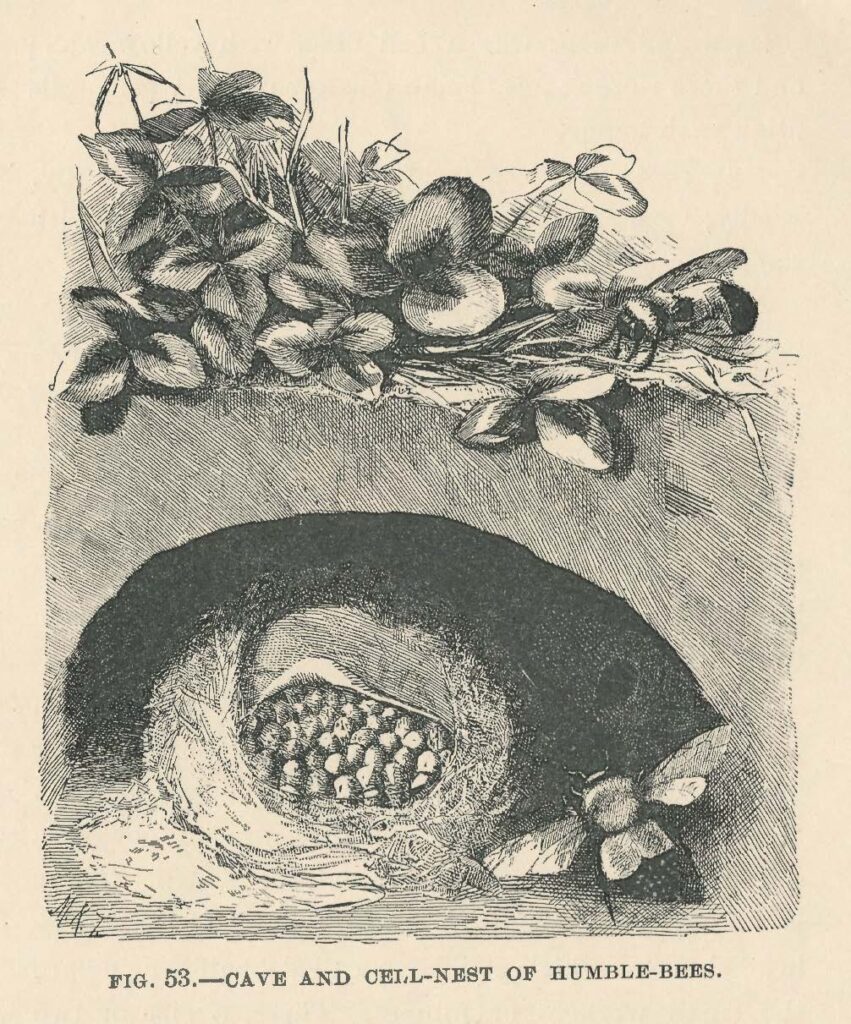

… plus this cross-section of ground-dwelling bumblebee nests:

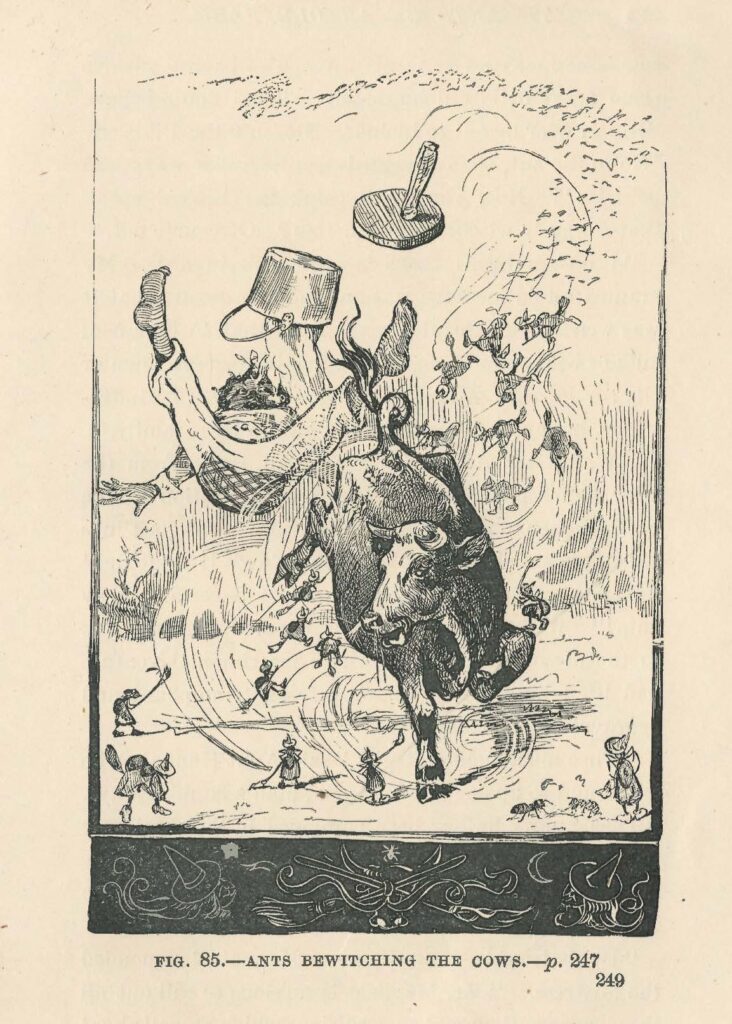

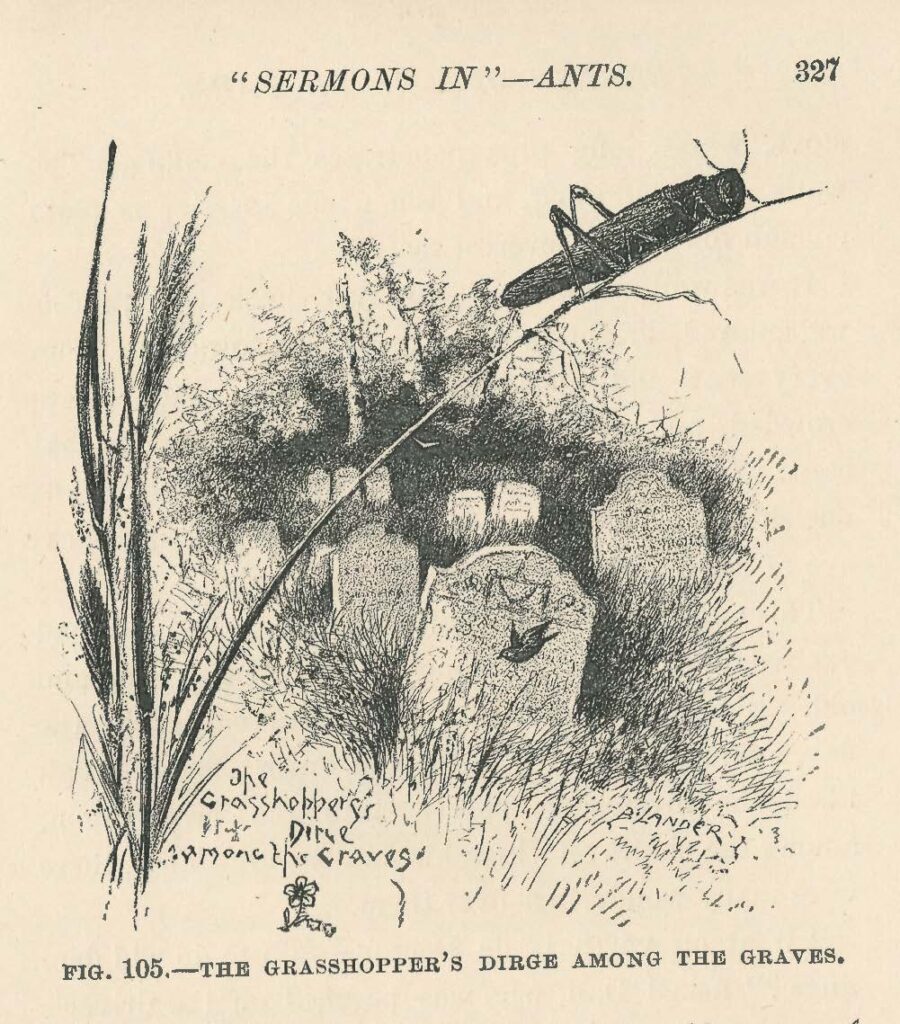

… and, finally, these two somewhat perplexing images (which make perfect sense in narrative context) of “Ants Bewitching the Cows” and “The Grasshopper’s Dirge Among the Graves:”

If you are interested in McCook’s work, the Biodiversity Heritage Library has several of his books and articles available in digital format. Tenants of an Old Farm is also available at the Internet Archive.