Wild Harvest: Sumac Season

A few days ago, while preparing staghorn sumac to dry for the winter, it occurred to me that sumac–whose tart berries, processed into a powder, are popular in Middle Eastern cooking and were once culinary and medical staples in First Nation and subsequent settler households–could make an interesting jelly.

Staghorn Sumac

Staghorn sumac–Rhus typhina–is a medium-sized shrub native to the Great Lakes region. Thickets of sumac, easily identified by fuzzy, antler-like branches, bright conical drupes ripening in late summer, and brilliant scarlet fall foliage, are a familiar sight along Ontario waysides. There is a popular belief that sumac is poisonous, but most varieties are not toxic, and staghorn and other edible varieties of sumac have a very long history of culinary, medical and social-ceremonial use. Sumac is reportedly a very high source of vitamin C: its most common traditional culinary use in North America is in a tart, cooling lemonade-like drink. In Middle Eastern cuisine, powdered sumac is nearly ubiquitous as a spice or condiment, and is well known as a principal ingredient in za’atar, to which it bestows its dark red colour and tart citrus-like taste.

Medically, sumac is reported to be a useful topical antiseptic and coagulant, and to have been widely used in traditional First Nations medicine. Sumac is also reported as an important ingredient in kinnikinnick, an herbal preparation used in social as well as ritual smoking. Among the print sources I have consulted so far, Robert K. Henderson’s The Neighbourhood Forager (Key Porter, 2000) offers the most detailed inventory of sumac’s reported traditional medical uses.

Sumac also has high concentrations of tannins, and the leaves and bark of certain sumac varieties have been widely used in Mediterranean leather-making for many centuries. In his fascinating, excellent book Make Ink: A Forager’s Guide to Natural Inkmaking (Abrams, 2018), Jason Logan passes over sumac in favour of black walnut for brown ink and pokeberry for a true red, but staghorn sumac’s ready accessibility, high tannin content and relative (certainly to the reportedly toxic pokeberry he chooses for its reliably crimson ink) make it a good option for experimentation with colour. Toronto container gardening expert Gayla Trail has reported success with using sumac berries to produce red dye, and the US Forest Service includes sumac as a traditional red dye source in its ethnobotany database.

Note: I am a geographer, not a botanist, and have an amateur-level knowledge of sumac, its uses, potential allergy interactions (sumac is reportedly related to the cashew plant and at least one source links it to mango) and potential risks. Before using sumac or any other wild plant, it is important to do your own research relying on high quality published sources.

Note also: In the Toronto area, sumac drupes usually reach peak ripeness in August or early September. The drupes are best if picked before rain. To avoid potential particulate contaminants from fuel exhaust, it is best to pick sumac away from busy highways. If you wish to harvest sumac, please trim the drupes carefully with a sharp blade rather than tearing them from the tree. Take only a few drupes from each tree, and leave plenty for wildlife.

Wild Apple Sumac Jelly

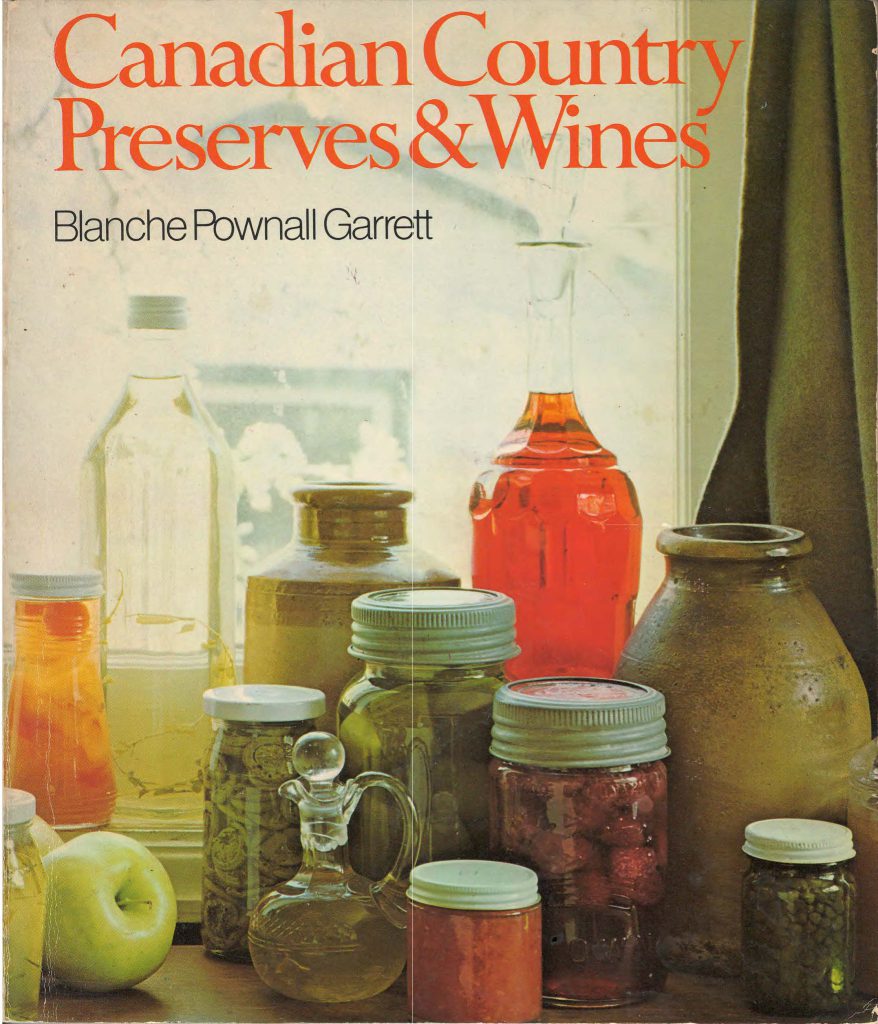

Sumac jelly references in published works are uncommon. My sumac jelly recipe is a modified version of a one published in Blanche Pownall Garrett’s Canadian Country Preserves & Wines (James Lewis & Samuel, Publishers, 1974), a book focusing on early settler foodways in Canada and early Canadian recipes. Sarah B. Hood’s excellent preserving guide, We Sure Can (Arsenal Pulp press, 2011), also includes a tested sumac jelly recipe that uses apple pectin, a natural alternative to commercial pectin. [Her book also includes an easy-to-make apple pectin recipe.]

Apple sumac jelly has a bright claret colour and a tart taste. The batch I made is delicious on sourdough toast. I plan to use it in place of cranberry sauce at Thanksgiving, as it seems to me it would suit turkey or chicken wonderfully. It would also be an ideal accompaniment to cheese.

Please note that I am an amateur and my recipe is based on a first-time experiment. For next summer’s batch I will almost certainly adjust it. If you are interested in trying sumac jelly, I recommend starting with the tested recipe in We Sure Can.

Ingredients

Sumac berries, 8 cups (from 8 to 12 whole drupes)

Wild or tart apples, 4 cups, stemmed and quartered

Water, about 12 cups

Commercial pectin crystals, 1 package (I used Certo)

Granulated sugar, 8 cups

Lemon juice, 1/4 cup (this may be optional, as the apples and sumac seem sufficiently acidic for food safety, but I included it to be sure)

Instructions

** This recipe makes 13-15 125 ml jars of apple sumac jelly (or 7 to 8 235/250 ml jars). It relies on well-established hot water canning techniques and easy-to-obtain equipment.**

Remove sumac berries from drupes. This is easily and fairly quickly done by drawing a fork downward through the drupes until the berries pop off. Some recipes recommend boiling the drupes whole, but it is my understanding that the stems are higher in tannins than the berries, and it is also easier to boil and process the sumac berries off the stem. A large sumac drupe can produce about 1 cup of berries.

Prepare jars in water bath canner: Wash jars and two-part lids in warm water with soap (I use Bernardin–Ball in the US–jars and lids with screw bands, which are readily available and highly reliable). Place jars in canner. Cover jars with two inches of water and bring to full rolling boil. Boil for 10 minutes. After boiling, turn off heat. Leave jars in, and drop in lids and screw bands. Remove just before filling with jelly. [Note: canning supplies, including large, non-reactive pots, jars and lids, funnels, jar lifters, magnetic lid lifters, etc. are sold inexpensively at Canadian Tire.]

Place sumac berries and apples in a large, *non-reactive* (e.g., stainless steel) pot. Cover with water, cover pot, and simmer until apples are soft, 15 to 20 minutes, stirring occasionally.

Using a sieve or colander lined with cheesecloth or a jelly bag, strain out liquid into a large bowl. Do not press or squeeze as it may make the jelly cloudy. If fine sumac hairs flow through the cheesecloth or jelly bag, sieve a second time. This should produce about 7 cups of apple-sumac liquid, a deep burgundy in colour.

Measure out 8 (yes, eight) cups of granulated sugar. [Note: if this seems like a lot of sugar, consider how jams and jellies are used: a spoonful at a time. Amortized over a year, especially if your diet is mainly healthy, this is a small quantity of sugar to add to your day, and is a lot less harmful than the high fructose corn syrup found in most commercially processed foods. If it still seems like a lot, low-sugar commercial pectins are available, as are homemade pectins. I have not tried them and cannot report on their efficacy at this time. I am not a fan of artificial sweeteners, however.]

Measure out 7 cups of liquid and pour into large, non-reactive pot (it is worth rinsing the pot first to remove any stray sumac fuzz). Stir in one package of pectin crystals (I used one 57 gram package of Certo brand pectin crystals). Bring to boil.

Pour in 8 (yes, 8!) cups of granulated sugar and 1/4 cup lemon juice (the lemon juice may be optional, as tart apples and sumac are high acid on their own) and return to a boil that cannot be stirred down. Boil hard for one minute or until the jelly’s set or gel point is reached (a candy thermometer showing 220 degrees Fahrenheit is one method; pouring out a few drops onto a cool plate to see if they ‘gel’ is another).

Remove and drain sterilized jars. Fill carefully with jelly mixture using canning funnel, leaving 1/4 inch head space. Using a non-reactive stick (I use a wooden chopstick), make sure there are no air bubbles trapped in the jelly. Carefully wipe rims of any stray drops (which may interfere with sealing). Carefully place lids on jars without touching their underside (this is why a magnetic lid lifter is a valuable tool). Spin on screw bands until resistance is met but do not overtighten.

Place jars in hot water bath. Jars should not be touching or tilted (when I make a larger bath of jam or jelly, I process the jars six or seven at a time, to ensure they all seal properly). Place lid on pot. Bring to a full-rolling boil and boil for 10 minutes (at elevations above sea level, you will need to boil longer: there are many guides online for boiling times at various elevations). After 10 minutes, turn off heat.

Using jar lifter, remove jars from hot water bath. Do not tilt, and do not touch or press lids. If the jars have sealed, the metal lid should ‘pop’ down audibly (this may take a few minutes). Do not touch for at least 12 hours. Jars that do not seal should be refrigerated and used within a week or two. Sealed jars should keep for a year, subject to the usual cautions about preserved foods.

Note: ‘traditional’ canning techniques involving paraffin wax, turning jars upside-down or using certain kinds of jars are no longer recommended as they do not meet contemporary food safety guidelines. The Government of Canada has published a very good overview of home preserving safety guidelines.

And also note: only low acid foods–foods whose combined acidity is less than 4.6 pH–can be preserved using water bath canning techniques. According to my research, apples usually have a pH under 4, and sumac has a low pH of about 2.5.

Sumac for Za’atar

My own introduction to sumac as an edible plant came in a recipe in a Middle Eastern cookbook that called for za’atar. I make fairly extensive use of (mainly European and North American) culinary herbs and spices, but had never heard of za’atar. Za’atar, it turns out, is quite easy to make at home–provided one has access to dried sumac. Fortuitously, I learned about za’atar in the early fall, when ripe sumac were still at their peak, and simply biked down to the lake to pick a few drupes for processing. Now, late every summer I pick a dozen or so sumac drupes to preserve for the year ahead.

Ingredients for dried Sumac

Ripe sumac drupes, about 8 to 12

Instructions

Strip berries from stems. Air dry in a wide, shallow dish for 1 to 2 weeks, turning occasionally.

In a food processor, pulse berries to separate fluff from seeds.

Using a food mill or sieve, separate berries from seeds. When completely dried, store in an airtight jar for up to a year.

For Za’atar

Note: dried sumac can be used on its own as a flavouring or condiment. In my experience its flavour becomes richer and more complex with storage. I use it whenever I make a Middle Eastern dish, and especially like to swirl it into the yoghurt sauces and dips that accompany many such recipes.

There are numerous recipes for za’atar available online. Za’atar and sumac are also available at many larger spice shops. I have read that in Israel and Arabic countries, most households will prepare their own blend, so it is worth experimenting.

Ingredients

Dried sumac

Oregano

Marjoram

Thyme

Sesame seeds

Salt

Instructions

Grind sesame seeds in a food mill or mortar & pestle.

Add additional ingredients and grind together.

Store in a sealed container.

Sumac for Drinking

There are two schools of thought on ‘sumac-ade’ or ‘sumac lemonade.’ The first suggests boiling the sumac berries with sugar to produce a syrup-like infusion. The second recommends against boiling sumac on the grounds that boiling will release tannins and produce a bitter taste. Interestingly, both techniques involve about the same quantity of sugar and in my experience produce a similar-tasting sumac drink. Simmering takes a bit longer, but ensures the sugar is fully dissolved and produces a richer, more complex, syrup-like flavour. But for a quick sumac drink, processing sumac berries and then infusing them into cold water or a pitcher of iced tea or lemonade seems a perfectly fine plan, and will likely preserve much of sumac’s reportedly high vitamin C content, likely degraded by heating.

For a ‘cold-pressed’ sumac drink

Sumac berries, 1 cup

Sugar, 1/4 to 1/2 cup (or to taste)

Water, 1-2 cups (for blending); plus enough to fill a pitcher afterward

In a blender, process sumac berries and water together until sumac berries are fully separated from seeds and liquid is quite dark. Strain liquid through muslin into a pitcher. Add sugar and water to fill pitcher. Stir well and serve.

For a boiled sumac syrup

Sumac berries, 2 cups

Sugar, 1-2 cups

water, about 4-6 cups

Optional: 1-2 tart apples, quartered

Place sumac berries in a non-reactive pot. Cover with water and add sugar. Bring to boil; lower temperature and simmer for about 10 minutes until berries are softened and mixture is dark and aromatic. Let cool. Strain liquid through cheesecloth to separate seeds and sumac hairs. Refrigerate. If covered and refrigerated, syrup should keep for up to a week. Add 1-2 tablespoons to a glass of water, or 1-2 cups to a pitcher for a sweet-tart drink rich in vitamin C.

Sumac Mead

Staghorn sumac is rich in malic acid, making it an ideal if unexpected candidate for wine-making. I have never tried it, but this recipe for sumac mead sounds delightful and even easier than making wine. I hope to try it out next month.

A Note on Foraging

I am so pleased with the results of my apple sumac jelly experiment. For the last several years I have made increasing efforts to use local, wild and untended plants that tend to be overlooked or even unwanted in urban settings. For years we have collected mulberries from street trees to make into ice cream or baked goods, and this year for the first time I made (delicious, especially when swirled into plain Greek yoghurt) mulberry jam. Last fall I made crabapple jelly, which was incandescent and lovely in every way.

Although I grew up harvesting wild plants and learning about their uses from my mother, I am not an admirer of the contemporary ‘foraging’ movement as commonly practiced, as it seems to lack adequate awareness of the most basic principles of conservation, despite paying lip service to them.

One example of destructive foraging is the extirpation in many areas of wild leeks, or ‘ramps’ resulting from enthusiasts (or pickers for commercial sale) trampling delicate forest floors and pillaging entire groves of plants. The problem has gotten so bad that the Province of Quebec has banned the commercial harvesting of wild leeks and several US states have implemented protective legislation.

I have also seen this happen with fiddleheads, whose overharvesting has denuded entire river bottoms where they were once plentiful. This is not even a new problem: in the 1980s my mother would run commercial harvesters out of ravine beside our house, after they descended in droves with large garbage bags they’d hoped to fill for commercial sale.

There are, however, many plants, particularly in cities, that may be harvested sustainably and even positively. Garlic mustard, for example, is an invasive plant in Ontario whose leaves reportedly make excellent pesto. Garlic mustard grows readily in disturbed soil and in parks and woodlots: pulling the plants and eating their prepared leaves is a positive act of conservation.

Crabapples and mulberry trees are common street trees in Toronto, where I live. For the most part they are ignored, except when their fruit falls on sidewalks and elicits public complaints. Picking and using their fruit is an excellent way to positively rethink their presence in cities.

There are numerous good published guides to edible wild plants: I have listed some in the Sources section at the end of this post. If you do good research, and if you harvest carefully and sustainably, it is possible to enjoy the fruits of the wild city.

Some Sources

Berglund, Berndt and Clare E. Bolsby, 1971. The Edible Wild. Pagurian Press. [A very good, reliable guide to wild plants in Canada and the US.]

Coon, Nelson, 1957. Using Wayside Plants. Hearthside Press. [A very good book on using wild plants for food, medicine, art, and crafts. If you can find any edition of this long out-of-print book second-hand, you are in for a treat.]

Garrett, Blanche Pownall, 1974. Canadian Country Preserves & Wines. James Lewis & Samuel. [A book exploring traditional Canadian foodways and recipes.]

Gibbons, Euell, 1962. Stalking the Wild Asparagus. Alan C. Hood & Company. [The ‘classic’ forager’s guide; highly worthwhile reading although not always reliable, and I have a few issues with material that appears borrowed from other published works.]

Henderson, Robert K., 2000. The Neighborhood Forager. Key Porter Books. [A very good introduction to urban foraging.]

Hood, Sarah B., 2011. We Sure Can: How Jams and Pickles are Reviving the Lure and Lore of Local Food. Arsenal Pulp Press. [An indispensable guide for anyone new to home preserving. Includes many tested recipes.]

Logan, Jason, 2018. Make Ink: A Forager’s Guide to Natural Inkmaking. Abrams. [A simply wonderful book about using wild, native plants to make inks.]

Moncrieff, Helena, 2018. The Fruitful City. ECW Press. [Moncrieff mentions sumac only in passing, but The Fruitful City offers a compelling case for making good use of the fruit trees that grow practically untended along urban streets and alleys.

Wild Harvest: Sumac Season Read More »